Sagua La Grande

Kicking off the Walk

We kick off the walk the day before at the museum of Sagua la Grande. We arrive late from festivities at the book fair in Santa Clara and with little ceremony, the museum director, a short, thin black woman smiling as wide as humanly possible ushers Miguel and me to the front of a long room filled with rows of chairs separated by a walking aisle.

We sit in the front row, across from a small table with two chairs.. The director of the museum faces the crowd and welcomes everyone.

“And,” she says smiling our way, “most importantly, welcome to Miguel Barnet and Guillermo Grenier, El Caminante, (the Walker) to this event commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of our most famous book.”

In our honor, she adds nodding to Miguel, she introduces a dancer in yellow who performs an enthusiastic Afro-Cuban dance, with the music provided by a black boom-box in on the floor. A young girl, early teens, takes the floor after the dancer. After a brief speech expressing the inspiration she received from the book and lauding my desire to transform it into a living experience, a walk that all Cubans could enjoy, presents Miguel and me with her original art work -- charcoal on parchment drawing of a cimarrón woman’s profile against a background of palms and machetes.

We move to sit behind the table as the museum director introduces us and gives us the floor. I speak first, presenting the project, nervously at first until my tongue loosened. My Spanish is always halting and oxidized during my first few presentations since I never prepare any text and just improvise from major point to major point. I distinguish between a “ruta,” or route, a well-trod and bureaucratic indicator of direction from place to place, and a “camino,” which the poets[1] (and Taoist teachings) tell us we make “al andar,” in the process of walking. Tomorrow we will take the first steps in establishing “el Camino del Cimarron.” I thank Sagua and those present for the opportunity and hope that it is just the beginning of establishing a path that others will follow. I hope they will remember the role of Esteban and the cimarróns in the creation of modern Cuba. The trail will create a geography of the biography, I conclude, each enriching the other.

My sometimes tongue twisted Spanish contrasts tragically with the eloquent prose that always finds a way out of the mouth of Miguel Barnet. He talks excitedly, as if for the first time, about meeting Esteban, gaining his trust, interviewing him, the surprise and pride he felt as the book gained respect. He speaks of the uniqueness of this project, its importance because it takes Esteban’s experiences from the pages of the book into the geography of Cuba, and of his gratitude to me for devoting so much time and passion to his work. Two cameras from local TV stations captured parts of the event for transmission in the evening news and maybe for posterity.

A local radio reporter, aggressive microphone in hand almost poking me in the face, is hell bent on understanding why I would do such a project, not living on the island.

“Why?” she asked. “Not living here. Not sharing our experiences, although you’re Cuban. Why do this?”

As a kid in Georgia, I was constantly reminded that I didn’t share the experiences of the natives as well. I didn’t know their songs, their histories. I had no knowledge of their heroes or a context for understanding their hatreds (of blacks for one). It was as if I was surrounded by inside jokes that I did not get. Same thing in Cuba, as it turns out, but without the sharp fangs.

“Why not?” I respond. “I might not live here but I care about Cuba. The people. My life turned out differently than yours, but we could easily be in each other’s shoes.”

She nods.

“Besides, it’s a trail that demands creation,” I say, “Se cae de la mata, (it’s ripe for the picking) to establish this trail. And,” I say with finality, “I like walking.”

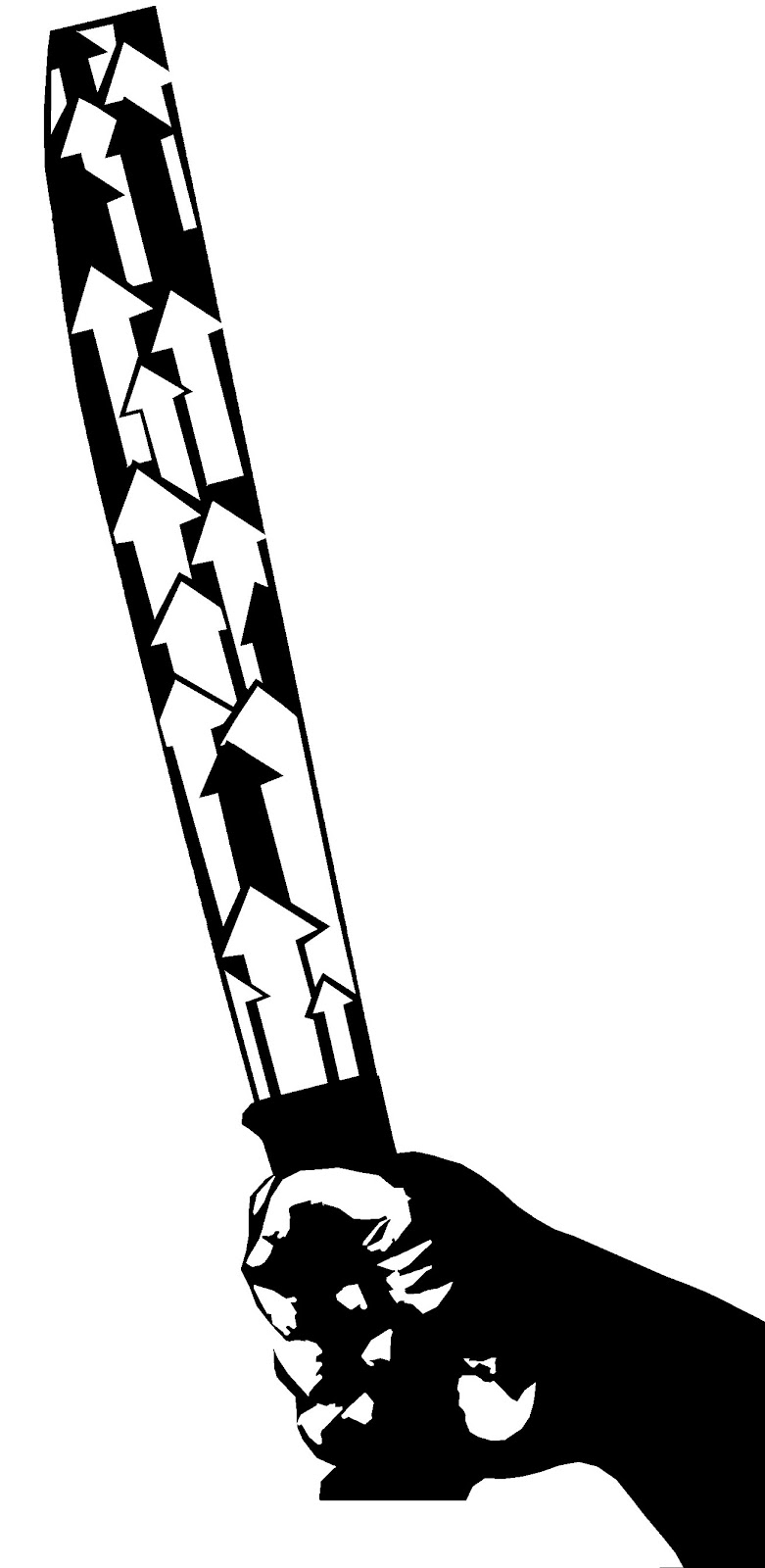

In an adjacent room, Miguel and I place, ceremoniously, a prototype of the symbol of the walk in an enclosed case in the museum, carefully, like placing a newborn baby in its crib, as the cameras whir. The symbol, which Miguel approved and likes, and I am lukewarm about, depicts a fist clenching a cane cutter’s machete. On the machete’s blade are embossed block style arrows pointing towards the tip.

Esteban, in the last line of the book declared boldly “Con un machete me basta.” All he needs is a machete to make his way in the world, no matter what the future holds. The arrows pointing to the tip of the machete represent the future that Esteban always faced with strength and confidence.

What we place inside the glass case in the museum of Sagua la Grande is a pretty anemic rendition of the significant metaphor of the machete in a clenched fist pointing towards a glorious future. Lazaro, Miguel’s assistant, called it a prototype; a small, ten-inch plastic model of a black machete and fist with white arrows on its blade.

“We could only get five made. They cost $50 each to make, so we have to be selective where we put them.”

“Fifty dollars!!” I say a little too loudly. Seems a bit steep for a plastic rendition of a machete in a clenched fist but maybe the arrows pointing towards the future, Miguel says dryly, spiked the price.

***

After the events at the museum, we cram into a dark blue Lada and ride across town to the historic Palo Monte Cabildo, Kunalungo. A crowd from the neighborhood mill in the at the entrance to the holy place, kicking up fine, smoke-like dust. Above the door of the white stucco house reads the sign “San Francisco de Asisis--Cabildo Kunalumbo, Sagua la Grande Fund. 1809”. The elder, dressed in a long dark blue-grey robe and matching ceremonial cap, with white tennis shoes, pants and shirt showing underneath, comes to the door. With arms outstretched he welcomes us to the historic place of worship. Maykel, historian of the region, speaks to the growing crowd of neighbors, giving an overview of the history and importance of the Cabildo.

"This part of Las Villas was called the conguería, Esteban Montejo told Miguel. And here we are. At the center of the “palero” cosmos, the very mecca. "Kunalumbo, I was there," goes a powerful palero prayer and now we are all here,” says Maykel to the crowd.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ah38wsQth6o

Maykel continues, “The famous scholar and anthropologist Fernando Ortiz came to the cabildo in 1947. Miguel Barnet,” he says point to Miguel, “made it to the conguería the March 26, 2016, on the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of the Biography of a Run-Away Slave.”

With that as a form of introduction, Miguel walks into the middle of the semi-circle that the crowd formed around the door to the Cabildo and speaks of his admiration and respect of the traditions maintained by the Cabildo.

“Now I’m going to say thank you, in a way that will make it clear what this place means to me.” He clears his throat and his voice rises in a Palo Monte chant [2]

He is ageless as he sings to the gods. I have seen him do it before at other ceremonial occasions. Each time I am impressed with his joy as he chants in the language of the ancestors. His voice rises in praise and falls abruptly to punctuate the end of some phrases. His right arm signals the highs and lows of the chant. He stops after a few minutes, saying, “I could go on through it all but it’s time to go inside.” The crowd love it. Applaud. He is in his ambiente; in his element.

Once inside, the priest motions towards the altar of San Francisco de Assisi, the patron saint of the Cabildo. He motions to me to approach the altar. I do so hesitantly. I ring the tiny bell on the floor beside me and ask for la bendicion, the blessing. I do want a blessing for the walk. I hope that San Francisco suffers fools.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uoRTtbZLwNs

**

“Do you want to go where Esteban was born, Miguel?” says Maykel.

“The infirmary of the sugar mill? That doesn’t exist anymore,”

“Yes it does. The footprint and some walls do. And the barrancones too.”

Two cars appear to take us to the old Santa Teresa sugar mill, today named Hector Rodriguez, in the neighborhood of Sitiecito, on the southern outskirts of Sagua. The mill is one of the oldest in the region, grinding sugar continuously for over two centuries. This is an industry bypassed by labor saving technology. All the production activity--smoke spewing from the smokestack, the cart loads of cane rolling in from the nearby fields and on the train tracks stretching into the center of the industrial complex--is much like it would have been during the late19th Century. Even the bell that called to work the parents of Estaban Montejo is still there, like a statue honoring some ancient tradition. Now a loudspeaker rings an electronic bell to signal the passing of the workday. Estaban remembered the importance of the bell in the daily routines of the slaves at the Flor de Sagua and all other mills where he worked.

Tomas Ribalta, the owner of the Maria Teresa, was Esteban’s first owner as well, even though Esteban was much too young to remember him. Ribalta had a reputation for being a comparatively compassionate slave owner. An enlightened owner of men and women when compared to other slave owners and the practices of the time. The slaves might have disagreed. The institution of slavery in the colonial context is ultimately about the total control of human beings, the deprivation of agency in the service of production and Ribalta contributed to the institution by building one of the few barrancones using the architectural design of a panopticon prison. All doors led to a large courtyard; the flow of slaves in and out of the slave quarters controlled by one arching gate.

We walk through the dirt streets of the batey. The batey is the equivalent of a company town where, before the Revolution, mill workers lived. Now, it is just a small settlement that happens to be on the grounds of the old mill. The residents, some who still work at the mill, look on as we walked past like archeologist exploring the ruins on which they live. These are the modern day barrancones. They look more like row houses. Open doors lead to a bustling world of cooking and rocking-chair-potatoes watching TV.

Miguel is clearly moved, eyes wide and misty, as Maykel leads us through the courtyard of the barrancones and the archway of the infirmary, all the while transporting us, with his monologue, to the epoc of Esteban.

“Like all children of slavery, I was born in an infirmary, where they’d take the pregnant black women to give birth,” remembered Esteban to Miguel. The infirmary is a large, square building, now segmented into small, apartment-like living quarters, reworked through the years but the exteriors with its white, dirt-poxed, stones still intact in some areas. We walk through a stone arch entrance into the vestibule, where the original walls are clearly visible. These were the walls that first welcomed Esteban Montejo to this world.

It was here that Esteban, like other babies born to slave women, spent the first years of life. The mothers were not mothers. They were breeders. After cutting the cord on the member of the next generation of the labor force, they returned to work as soon as they could walk. The babies stayed. When they turned six or seven, they resettled in the barrancones and began their work lives as slaves. The process of weaning the mother from her natural mothering tendencies must have been horrendous. Like a lobotomy taking years to complete.

“I had never been here,” says Miguel, as he walks into the patio of the infirmary, as if traveling back into the 19th Century. “I didn’t know this place existed.”

Esteban remembered his birth date because his godparents, Gin Congo and Susana made sure that he knew: December twenty-six, 1860, the day of San Esteban. His father was named Nazario, a Lucumi Yaruba from Oyo, a settlement in today’s Nigeria. His mother was Emilia Montejo, a slave of French origins. Why he kept her name is not explained but probably because the slavers gave an ethnic name to his father, stripping him of his actual name.[4]

His birth was unremarkable in anything other than his survival. In the big scheme of things, the birth of another slave in Cuba did not create a social ripple of any kind. According to the 1861 Census, Estaban joined the army in chains of 375,000 to 400,000 African origin slaves creating the Cuban economic boom based on sugar production. [5]

This is the geography where our story really begins.

[1] Here I was thinking of the most famous poet that reminds us of our power to create our destiny, creating our own path; Antonio Machado in his poem “Caminante, no hay camino” (Walker, there is no path), where he reminds us that “se hace camino al andar” (the path is made as you walk).

[2] Palo is a religion brought to Cuba by central African slaves from the Congo basin which venerates ancestor worship and the powers of the natural world. There are various branches of the religion, each syncretizing with Catholicism in some way. The Cabildo de Nación Kunalumbo, Sociadad San Francisco de Asisis is considered to be the oldest Palo Monte Cabildo in Cuba, founded in 1809. Other Cabildos, particularly in Santiago de Cuba, dispute this foundational designation.

[3] All quotes are taken from Biography of a Runaway Slave by Miguel Barnet. Curbstone Books; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, Illinois. 2016. Fiftieth Anniversary Edition. Translated from the Spanish by W. Nick Hill. Introduction by William Luis.

[4] Slave names followed an accountability formula, particularly for male slaves. Slavers needed to identify them easily but maintain a certain mercantilistic ability to differentiate the product, the slave. The intention of the first name was to facilitate assimilation into Christian society. But the last name referred to the ethnic origin of the individual slave. So while there might be many Franciscos, notably fewer slaves would answer to Francisco Congo, or Lucumi, or Mondongo, or Ganga, etc.

[5] Kiple, Kenneth F. Blacks in Colonial Cuba: 1774-1899. The University Presses of Florida: Gainesville Florida. 1976:63.

No comments:

Post a Comment